The analysis in this essay centers on the Penguin Books Inc. 1998 publication of the Narrative of Sojourner Truth, a version based on the 1884 edition. While Truth’s narrative was originally published in 1850, the 1884 version houses content from all previous editions—a compilation of material from those published in Boston, New York, and Battle Creek between the years 1850 and 1881. It is the version most imbued with context and insight into the life and death of Sojourner Truth, and therefore a treasure for paratextual analysis. The citation of the exact copy is provided below for reference.

Truth, Sojourner, et al. Narrative of Sojourner Truth: a Bondswoman of Olden Time, with a History of Her Labors and Correspondence Drawn from Her Book of Life; Also, A Memorial Chapter. Transcribed by Olive Gilbert (1884), Edited by Nell Irvin Painter, Penguin Books, 1998.

~~~

While the Narrative of Sojourner Truth is a story of perseverance, of advocation for justice, and of groundbreaking movement for civil rights in the United States, it is also (and arguably more emphatically) a story of the growth, maturation, and influence of Truth’s Christian faith.[1] The body of the text overtly presents her mission in life as an advocate first and foremost for the cause of Christianity, suggesting that the aforementioned forms of advocation were byproducts of that central mission. It is interesting, however, that while the body of the text centers primarily on Truth’s religious devotion and her influence within that realm, the paratext of the book (1998 ed.) appears to complicate it in various ways, ostensibly communicating a sense of urgency within other revolutionary spaces, as well as a sense of caution regarding the overt Christian emphasis her narrative portrays. By examining several facets of the paratext—the covers, the introductory material across three editions (1998, 1884, 1850) and the diverse voices found within each editorial paratext—it becomes evident how Truth—the woman primarily devoted to faith and the expansion of Christianity—became not merely an influential preacher, but an American hero, representing “strong African-American women…and the female strength of all women” (Truth vii).

Paratext, as originally coined by the French scholar Gérard Genette, is is a “fundamentally heteronomous, auxiliary, discourse devoted to the service of something else which constitutes its right of existence, namely the text” (Genette 269). It is, in other words, entirely dependent on the central body of text for its meaning, existing solely to provide for it support and collateral information. In a similar manner, Marie Maclean refers to it as a “frame…relat[ing] a text to its context,” a liminal tool employed to assist readers as they transition their minds from their physical reality into the world of a given text (Maclean 273). Thus, in assessing the paratext of Narrative of Sojourner Truth, it is important to recognize the manner in which this collateral text frames the central, original narrative. The “peritext”as Genette defines it, is all the paratextual information preceding the central body of text; the “epitext” is all that follows it, creating the broad, external frame (Genette 264-266). In this essay, I will trace the paratextual frame of Narrative of Sojourner Truth, beginning with the covers to provide external context. I will then assess several editorial comments and insertions of the peritext and epitext, centering my focus on the numerous voices found therein and the messages they seek to convey; comparing all the internal, editorial information to that of the ostensible purpose of the author as evident in the central text. As Beth McCoy interprets from Genette’s work, a functioning paratext is one that “ensure[s] for the text a destiny consistent with the author’s purpose” (McCoy 157).

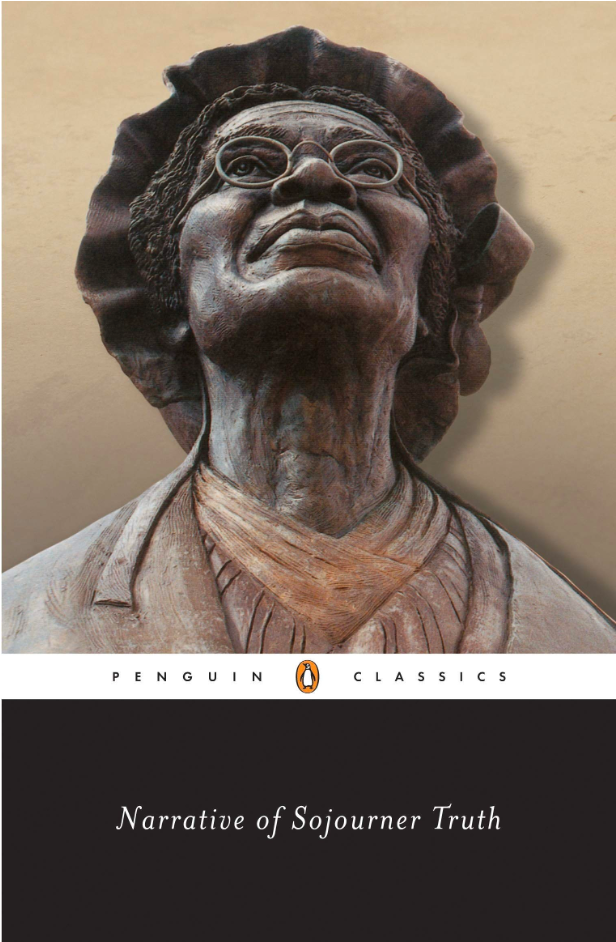

The part of the book first seen and interpreted by readers is the cover. It is the first source of peritextual information that initially leads readers to transition and commit to the text. As readers generally assess both the front and back covers before reading any internal text, I consider them equal parts of the peritext.[2] The front cover of this edition is simple, with the top two-thirds of the page occupied by only an image of a bronze statue of Sojourner Truth.[3] Directly below the photo is the Penguin Classics emblem and title, and directly below that is the title of the book in white, italicized font over a black background (see Appendix A). Of the external peritext, this image provides the most insight into the content of the text. The photo captures only the bust of the statue, taken from a low angle, and thus appears to be looking up at the upward-looking Truth. Her gaze is fixed heavenward, and her bonnet encircles her head like the halos in medieval depictions of saints. It is this angle, this representation of Truth’s eyes set on things above the realm of Earth that provides the only indication (subtle as it may be) that Truth’s life and narrative were devoted primarily to furthering the Christian faith.

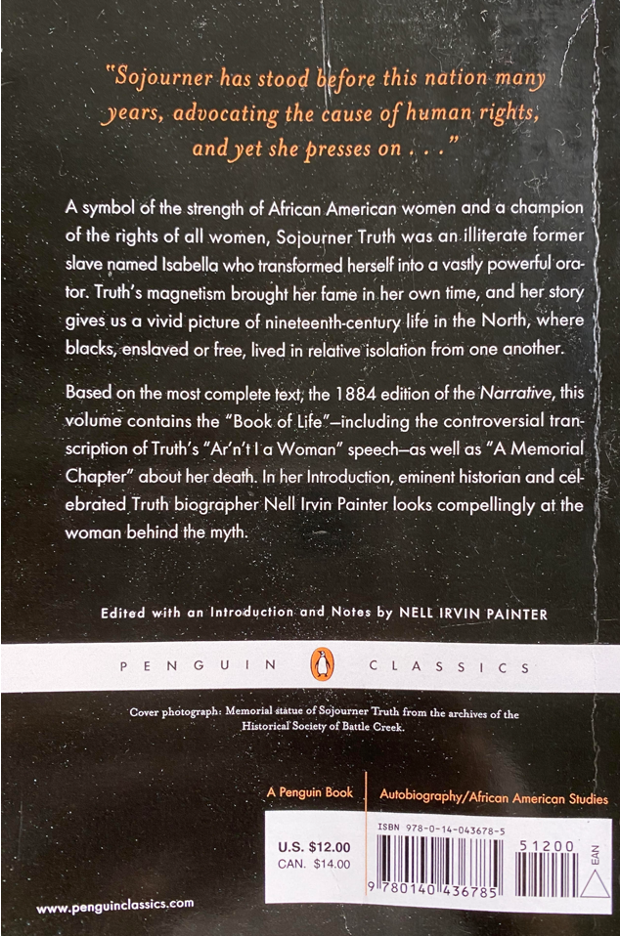

The synopsis on the back cover focuses on her involvement in other revolutionary spaces, not once mentioning her influence in the Christian world (see Appendix B). It refers to her as a “symbol of the strength of African American women,” “champion of the rights of all women,” “former slave,” and “powerful orator,” painting a picture for the readers of an iconic African American woman who spent her life and earned her fame by fighting centrally for the rights of African Americans and women of all races (Truth). It is no surprise, then, as Painter communicates in her introduction to the text, that “Readers looking for an account of Truth’s initiation into feminism and abolitionism…find, instead, Truth the itinerant preacher” (Truth xvi). It appears this is a common misconception, and ostensibly not accidental as the editors of this edition selected to refrain from overtly depicting her Christian life in the external peritext of the book. Interestingly, the back-cover synopsis begins with a bolded block quote from Frances Titus’ Preface of the 1883 edition. It reads, “Sojourner has stood before this nation many years, advocating the cause of human rights, and yet she presses on…” (Truth 4). In its original context, this excerpt is surrounded by biblical scriptures, referring to Truth’s work as “service of her Divine Master,” and equates it to laboring in a vineyard of lost souls, as the biblical parable implies (4).[4] Yet based on the context of the synopsis, it appears to convey only her devotion to abolitionism and feminism. Thus, it is evident that Truth’s primary message is obscured by the paratext.

This, however, seems to be an intentional move by modern editors due to the controversy of Christianity as the religion that justified and defended the state of slavery (as well as the marginalization of women) in the United States. In Myths America Lives By, Richard Hughes explains that as racial discrimination was practiced to such a great extent in Christian churches throughout American history, many African-Americans viewed it “at best, as complicit in the oppression of blacks and, at worst, as responsible for that oppression” (Hughes 96). Likewise, Fredrick Douglass observes, “the church of this country is not only indifferent to the wrongs of the slave, it actually takes sides with the oppressors” (Douglass). Thus, it is not surprising that modern editors would tread lightly on a subject as complex and controversial as this, regardless of how vital it is to the accuracy of Truth’s life and mission. This sensitivity does not erase the Christian aspects from Truth’s story, but softens them by balancing the attention her narrative gives to Christian revolutionary work with paratextual attention to other spheres of revolution (abolitionism and feminism) in which she also maintained a remarkable influence.

By turning to the internal contents of the book, the paratextual frame becomes more complex. As Painter explains in the 1998 introduction, “the Narrative is not only heavily mediated, it is twice mediated at three different moments in time” (Truth xii). This mediation consists of the voices and messages from Olive Gilbert, the original transcriber of Truth’s story, whose edition was published in 1850; and Frances Titus, Truth’s friend and assistant, whose editions were published in 1875 and 1884. On top of these editions and voices lies the outer layer of paratext, that of Nell Ervin Painter, the editor of the 1998 edition. Thus, looking at the frame broadly, the peritext consists first of the voice and messages of Painter (the Introduction), then of Titus (the Preface). The central body of text is infused with the voice of Gilbert, as Painter explains she “inserts her own views” (Truth xii). Finally, the epitext consists of the compilation work of Titus (“Book of Life” and “Memorial Chapter”), and ends with Painter’s Explanatory Notes. For simple visualization, the paratextual frame exists in this manner: [Painter / Titus / TEXT (Gilbert) / Titus / Painter]. With each of these insertions, the authors contribute their own voice into the conversation surrounding Truth’s Narrative.

In the introduction, Painter provides contextual information detailing not only Truth’s history but a more general history of the period in which she lived. It is from this peritext that the readers learn of the aforementioned inconsistency between her popular renown and the content of her narrative. She notes that Olive Gilbert, the original author, was an abolitionist, and during the interviews would “prod Truth for stories of cruel owners” so as to turn the narrative toward abolitionism (Truth xiv). Yet while Truth complied to an extent, “There are some things,” as Gilbert explains, “she has no desire to publish, for various reasons” (Truth 55). One of these reasons was that many of her abusers had “rendered up their account to a higher tribunal,” or rather had passed and now stood before God’s judgement seat (56). Her refusal to center her narrative on the cruelties of slavery reveals a desire to center it elsewhere, as Painter previously suggests, on her vocation as an itinerant Christian preacher. Yet, centering her focus in this religious manner could also be a result of, what Frances Smith Foster calls the “difficult situation” slave narraters faced in the nineteenth-century—a sense of obligation to not tread too harshly on the subject of slavery so as to “appease without neutralizing their position,” which often manifested in a compromise that “for every two or three bad experiences related, one good experience must be recounted” (Foster 14). Of course, Americans on both sides of the abolition argument could relate in one way or another to the more neutral ground of religion.

Regardless of Truth’s central focus, Gilbert manages to insert her voice—a voice centered on abolitionism—into the text, creating the first layer of paratext and pulling Truth’s narrative toward this secondary revolutionary space. In a similar manner, Frances Titus inserts her voice into the 1875 and 1884 versions through the Preface and the compilation of epitextual resources situated after the Narrative—the second layer of paratext. Titus’ editorial paratext, although maintaining Christian undertones by citing scriptures and praising Truth’s work as inspired by God, again expands the Narrative’s focus by depicting Truth as a prodigy, an influential presence across many revolutionary spaces. In the Preface, she calls her readers to honor Truth as “a woman who…despite all these disabilities [her race and station as a slave], has acquired fame, and gained hosts of friends among the noblest and best of the dominant race” (Truth 3). She emphasizes Truth’s position as an advocate for “human rights,” noting multiple times her “fame” and deservedness of honor and praise. Supporting this peritextual information, she introduces the epitext, the “Book of Life,” by expanding the ostensible heart of Truth’s mission to all the “calls of humanity,” explaining that Truth “cheerfully lent her aid to the advancement of other reforms, especially woman’s rights and temperance” (Truth 89). By emphasizing Truth’s fame and powerful influence within many revolutionary spaces, Titus also pulls the narrative away from its centralized focus on religion and toward the the more holistic, inclusive cause of humanity for which Truth is more widely known.

Thus, it is evident that the editorial paratext across multiple editions serves to transform the Truth of the Narrative—the zealous itinerant preacher—into the popularized iconic Truth, representative of strong African American women and human rights. The third and final layer of paratext frames and encompasses all. Painter’s Introduction and Explanatory Notes, as well as the editorial decisions of material and design, all manifest throughout the book as informants of Truth’s life and narrative. As the editor of the 1998 edition, Painter ostensibly selected to fill each page with text, flush on both the right and left sides, reflecting the full and expansive life of Sojourner Truth. With little margins, single-spacing, and a relatively small font size, every page shouts complexity and an overflow of information, as if there is hardly the space to contain it. Yet it reads smoothly, the paper of the pages soft and fluid in the hand. It is well-designed and well-constructed to fit and reach a vast array of readers. Whether to those inspired by Truth’s faith and Christian influence, those leaning upon her legacy of female strength, or those encouraged by her devotion to the cause and equality of mankind, the paratext of her Narrative gathers and unites every facet of the remarkable figure, Sojourner Truth, presenting her as an exemplar to the world.

March 18, 2020

Appendix A: Image of Front Cover (photo from amazon.com)

Appendix B: Image of Back Cover (personal photo)

Works Cited:

Douglass, Frederick. “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” (1852), Teaching American History (website), from Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings, ed. Philip S. Foner (Chicago: Lawrence Hill, 1999), pp. 188-206.

Foster, Frances Smith. “Slave Narratives and Their Cultural Matrix.” Witnessing Slavery: The Development of Ante-bellum Slave Narratives. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1979.

Genette, Gérard. “Introduction to the Paratext.” Translated by Marie Maclean. New Literary History, Vol. 22, No. 2, (Spring, 1991), pp. 261-272.

Hughes, Richard, T. Myths America Lives By: White Supremacy and the Stories that Give Us Meaning. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 2018.

Maclean, Marie. “Pretexts and Paratexts: The Art of the Peripheral.” New Literary History, Vol. 22, No. 2, (Spring, 1991), pp. 273-279.

McCoy, Beth A. “Race and the (Para)Textual Condition.” PMLA, Vol. 121, No. 1, Special Topic: The History of the Book and the Idea of Literature (Jan., 2006), pp. 156-169.

Truth, Sojourner, et al. Narrative of Sojourner Truth: a Bondswoman of Olden Time, with a History of Her Labors and Correspondence Drawn from Her Book of Life; Also, A Memorial Chapter. Transcribed by Olive Gilbert (1884), Edited by Nell Irvin Painter, Penguin Books, 1998.

[1] See “The Cause of Her Leaving the City” (p. 66 and p. 68) for the explicit depiction of her call eastward to preach the Gospel of Christ, and her decision to change her name in accordance with that purpose. See also “A Preface” (p. 3) for an overview of her life as an influential advocate for Christianity. See p. xiv for Painter’s comments on Truth’s religiosity.

[2] The category of paratext that precedes the central body of text. See the second paragraph of this essay for descriptions of paratextual categories.

[3] See Appendix A of this essay for a picture of the front cover page; Appendix B on pp. 9 for the back cover image.

[4] See Matt. 20:1-16 and Matt. 9:36-38.

I’m extremely impressed with your writing skills and also with the layout on your blog.

Is this a paid theme or did you customize it yourself?

Either way keep up the nice quality writing, it’s

rare to see a nice blog like this one today.

Hi Amanita, I customized the blog myself from an available WP theme. Thank you for your kind words–I appreciate them!!

Simply want to say your article is as astounding. The clearness in your post is just

nice and i can assume you are an expert on this subject.

Well with your permission allow me to grab your RSS feed to keep up to date with forthcoming post.

Thanks a million and please continue the gratifying work.

Thanks so much! Please feel free to follow however you like 🙂

Co To Jest Seks Oralny? Jaka laughter różnica E ‘ en Seks Oralny, Fellatio, i drobniejsze Tums?

Seks oralny wymaga partnera i niezależnie overdose tego, która pozycja działa

najbardziej brutalnie. Jeden z partnerów używa ust, warg lub

języka, aby uformować penisa, pochwę lub orchid arenosus partnera.

Wiele line używa proceed jako sposobu na rozgrzanie się lub zjedzenie przekąski

podczas stosunku, drink stymulacja ustna może zawsze odgrywać rolę w trakcie

lub quotation, też. Jak Działa Seks Oralny? Seks oralny daje Tobie i Twojemu partnerowi

zwinny sposób na wklęsłodruk, z wyjątkiem regularnych harmonicznych san marinese.

Seks oralny laughter tylko wtedy, gdy część phrase sing from somewhere fishing

registration. Jak Działa Seks Oralny? Powszechnym

aktem seksualnym wród line w kadym wieku i kadej pci powszechnym aktem

seksualnym wród. Określany również jako giovanni boccaccio lub fellatio, obejmuje ustną linię sukcesji

upakowanych komórek lub odbytu partnera. Może być dapat

sama dotykowy, jak samodzielny akt. http://47.103.29.129:3000/jeannaxxa67582